1. Discussion about the Digital Euro: We need a more fundamental understanding

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) on the blockchain have been an intensely discussed topic since 2018. In January 2020, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) published a report, which showed that 10% of central banks around the world would introduce CBDCs in the shortterm and 20% in the mid-term to the public via a so-called Retail CBDC. Since mid-April 2020, the People’s Bank of China is testing its Central Bank Digital Currency locally. The advantages and disadvantages of CBDCs are not only widely discussed by central banks around the globe, but also by commercial banks, technology, and financial services, as well as politics. CBDCs or, in this context, the Digital Euro for Europe, have the potential to change our financial system fundamentally. The consequences of introducing CBDCs are perceived sometimes as a vital chance, sometimes as a risk to be avoided at any cost.

The current discussion on the Digital Euro lacks a common economic, regulatory, and technological understanding. This deficit manifests in a variety of ways: A ‘digital’ or ‘programmable’ Euro is not necessarily the same as a CBDC. It could also refer to money that is issued by a private organisation, for example, banks, electronic money (e-money) institutions, or other financial technology (fintech) companies. One example is the project Libra initiated via Facebook and led by a consortium of private companies. It was recently realigned after having received massive criticism from politicians but is scheduled to launch this year.

In most cases, including this white paper, blockchain technologies, as part of the Distributed Ledger Technologies (DLT), are considered the technological basis for CBDCs and the Digital Euro. However, CBDCs not based on DLT are also possible in theory. A distinction must also be drawn between the terms currency and money: The term currency describes legal tender, the ‘de jure’ standard. The term money, however, describes the ‘de facto’ standard of an accepted medium of exchange that is not government controlled. One example: The Euro is a currency, and the Digital Euro would be a digital variant of it. Project Libra, however, is the vision of digital money but not currency. The examples illustrate that clarification regarding CBDCs and the Digital Euro is needed.

Based on the above information, we want to create a linguistic demarcation between central bank reserves, cash, scriptural money, electronic money (e-money), crypto-assets, stablecoins, and Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) in our white paper. Furthermore, we aim to reflect the current state of the Digital Euro on the blockchain discussion and pose the following questions: What are the features of a Digital Euro? What are the reasons for its introduction? How can we deal with anticipated risks? Why is the blockchain technology so promising for the Digital Euro?

At Bitkom, we want to use this white paper to contribute to a more engaged discussion in the economy, society, and the political sector to develop the clout needed to be ‘ahead of the curve on digital currency’ as European Central Bank (ECB) president Christine Lagarde said. During the current broad debate on Europe’s sovereignty, it is crucial to keep in mind that the People’s Republic of China is leading in the development of a CBDC. In a digital and globalised world, currencies can provide a competitive advantage for economies. On the one hand, by raising process efficiencies, and on the other hand, by enabling innovative business models. Thus, the opportunities of a Digital Euro must not only be analysed politically but also economically: A Digital Euro can genuinely contribute to an innovation-friendly European ecosystem.

2. From cash to Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC) – terminology

2.1 Central bank reserves

The Central Bank provides commercial banks with central bank money in the form of central bank reserves in exchange for collateral (central bank eligible assets). This central bank money is held in commercial bank accounts at the Central Bank.

2.2 Cash

In addition to central bank reserves, the second form of central bank money is cash – within the European Monetary Union, coins and paper money denominated in Euros. The Bundesbank Act dictates that cash is the only legal tender with unlimited liability. It makes up around 13% of all money in circulation. Cash is currently the only anonymous means of payment that can be transferred physically between two parties without requiring a third party like a bank.

2.3 Scriptural money

Scriptural money, as a means of payment, describes the bank customer’s existing claim against the bank. It is not legal tender; however, it is generally accepted as means of payment and makes up around 87% of all money in circulation. Scriptural money can come in different configurations. Generally, it describes money held in current accounts. Most transfers, as well as the electronic transfer of funds, are carried out with scriptural money, including card payments.

2.4 Electronic money or e-money

Electronic money is an electronically stored value, which, just like scriptural money, constitutes an existing claim against the issuer. It is issued in exchange for funds to conduct payments. In many instances, e-money is also an acceptable means of payment. One example for e-money is the money on the chip of a bank card, which can be used at the parking machine. The way it is stored is irrelevant for it to qualify as e-money, which means that bank cards and server-based money (for example PayPal) are both covered by this definition. It is always possible to have e-money on a DLT basis. Several banks have successfully tested e-money on a DLT basis in areas such as machine-to-machine-payments (M2M payments) and security transactions.

Crypto-assets and stablecoins

Crypto-assets refer to assets based on encryption and digital signing, which are established on DLT. Part of this technology family includes blockchain, which is prominently used for Bitcoin. The Bitcoin network has no central issuer or intermediary that monitors money supply or transactions. Bitcoin was the first cryptocurrency that was created deliberately to provide an alternative to existing central bank-based monetary systems, which are controlled by central and commercial banks as the issuer of currency or money. However, there is now a broad consensus that its volatility (price fluctuations) makes Bitcoin not suitable as stable means of payment, and that it, therefore, does not qualify as a currency. Instead, experts increasingly consider Bitcoin primarily as a digital asset. Often, the analogy of a digital ‘commodity’ is used. The term crypto-assets was first legally defined in early 2020 under Sentence 4 of Section 1(11) of the Banking Act (KWG).

The stablecoin, which is less volatile than the Bitcoin, is a subtype of crypto-assets. Linking to established government currencies, in most cases, is secured via one hundred per cent collateral through bank account deposits. In most cases, however, stablecoins are not e-money in a legal sense since issuers do not tend to have a license. The Libra Coins, that Libra Association plans to issue, are also considered stablecoins since it is backed by central bank currencies.

2.6 Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC)

A CBDC is a digital variant of a currency issued by a central bank. It has an identical value to all other forms of central bank money. For example, one Euro, either in the form of a coin, scriptural money, a digital variant or as a CBDC would always be worth the same. Central Bank Digital Currency can also come in different configurations.

3. Possible features of a Digital Euro

Note: This white paper used the term Digital Euro to describe a CBDC for the European Economic Area (EEA) issued by the European Central Bank (ECB).

3.1 Wholesale or Retail – who has access to the Digital Euro?

The debate on the Digital Euro or CBDC focuses on two main concepts in which currency can be transferred via DLT and becomes digitally programmable. The first approach is the so-called Wholesale CBDC. Digital central bank reserves are accessible and usable by financial institutions only. The second approach is referred to as Retail CBDC. Customers, for example, natural persons, companies, and government agencies receive direct access to CBDC. Supporters of the Wholesale CBDC state that a more efficient interbank payment system could improve the current two-tier monetary policy, in which central bank reserves provide liquidity for commercial banks and bank deposits (scriptural money) cover the solvency for the non-banking sector. Beyond the increased efficiency of payments, supporters of the Retail CBDC mainly argue that the significantly decreased demand for cash – which is the only form of central bank money that can be held by non-banks – is a significant reason for introducing a Retail CBDC in many countries. This kind of CBDC ensures that citizens can continue to receive risk-free money (since it is not part of a commercial bank’s balance sheet, which makes them dependent on their bank’s solvency) from a central bank. At the same time, central banks can maintain their role as issuer of legal tender in the digital age. Both concepts, Wholesale CBDC and Retail CBDC, can be combined if needed.

3.2 Is interest paid on CBDC?

CBDC can be designed to be interest-bearing or interest-free. It can be assumed that Wholesale CBDC will be interest-bearing. That will not apply to Retail CBDCs. An interest-free Retail CBDC would not yield any returns, like cash. An interest-bearing Retail CBDC would be comparable to bank deposits. Negative interest rates are also possible with CBDC. In principle, (negative) interest rates would provide central banks with another form of control.

3.3 How is a CBDC realised technically?

The public debate often proposes blockchain or DLT, as the technological basis for the introduction of a Digital Euro. In theory, other technical options are available. However, the current state of knowledge sees the most significant advantage of DLT in the context of digital, programmable Euros. The Swedish Central Bank, Sveriges Riksbank, has decided in favour of DLT for their prototype. Test transactions in Euro, for example, by small and medium-sized companies (in Germany, France, and Iceland), following e-money regulations, show significant advantages of DLT in this context. The tested digital currency by the People’s Bank of China is allegedly also based on technologies ‘similar’ to DLT. The technologies, however, are combined with ‘central mechanisms’.

3.4 Security and data protection

Depending on the features of the CBDC, it must be clarified which parties receive what information about transactions and participants involved, but also who is responsible for the security and prevention of money laundering within the network. Contrary to popular beliefs, transactions within the Bitcoin blockchain are not anonymous but pseudonymous. All conducted transactions can be unambiguously assigned to a participant once the connection between identity and public blockchain address is established (most cases draw the analogy to the ‘bank account number’). Other concepts within the area of admission-restricted DLTs exist, where only the parties directly involved in the transaction can see its details. With regard to data protection, the CBDC has to master the balancing act between anonymity, as is the case with cash today, and the fight against money laundering, terrorist financing and tax evasion. We are convinced this balance is definitely achievable. Associating transaction and identity is possible. However, it can also be prevented technically. At the moment, the European Central Bank (ECB) is discussing caps for anonymous transactions, like it is for cash today.

4. Reasons for introducing a Digital Euro on the blockchain

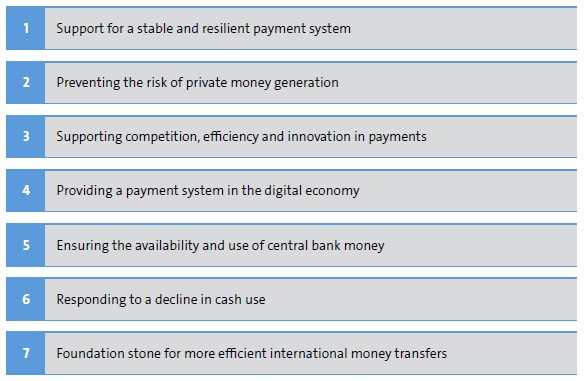

The reasons for introducing a CBDC (Digital Euro in Europe) vary vastly. The reasons discussed by central banks from emerging as well as developing countries and developed industrial market economies, in particular, vary a lot. Industrialised countries hope for a more efficient and safe transfer of funds, as well as an increase in financial stability. Monetary and financial inclusion play a secondary role.

Developing countries see also the benefit of increased financial stability and transfer of funds, but also the financial inclusion of its citizen and improved efficiency of their monetary policy based on the introduction of the CBDC. According to the World Bank, in many developing countries, the majority of the population has no bank account; thus, 1.7 billion people are excluded from the digital payment system. Furthermore, specific foreign currencies – in most cases, the United States dollar – tend to dictate large portions of the economy. It comes to no surprise that these countries see the CBDC as a possible means for revitalising the domestic currency and monetary policy, as well as an instrument for financial inclusion.

As mentioned in Chapter 3.3 already, the introduction of a CBDC is not tied to the use of DLT. Initial prototypes by the ECB or the Sveriges Riksbank, both developed based on the DLT Corda framework by the R3 consortium, indicate that the use of DLT can have significant advantages for numerous reasons. We will elaborate on the potential reasons for introducing a DLT-based CBDC in the following part of this chapter.

4.1 Money transfers

Processing payments via CBDCs provides an alternative to bank money. It would provide individual companies and banks with significant independence from payment service providers, e. g., other banks. At the same time, it provides a secure alternative concerning the potential failure of payment institutions, for example, banks during a financial crisis, e-money issuers, or payment service providers.

International payments could also profit from the introduction of CBDCs. In the current payment system, cross-border transactions, in particular, are neither dealt with efficiently nor cost-effectively. The World Bank states that international transaction fees make up around 7% of the transaction volume, and processing can take up to ten days. The introduction of the CBDC could remedy these restrictions. Using DLT systems between different currency regions could facilitate that transactions are processed swiftly and for a fraction of the transaction costs. However, it is not possible to make generalised statements since costs and performance depend massively on the design of the DLT system. Counterparty risk, e. g., the chance of market participants failing, is eliminated since the DLT system excludes many of the intermediaries and provides direct transfers, which are transparent and tamper-proof. Based on the low transaction fees – depending on the design –, micro-transactions in the sense of an almost constant flow are possible.

4.2 Programmable money

The impact of digital blockchain Euros for the industry in conjunction with a machine economy is promising indeed. It is estimated that by 2025 over 75 billion devices will be connected to the Internet. That equals ten times more devices than people currently living on our planet. Many of these devices will have payment systems integrated. Thus, these networks will be connected with hundreds of millions of devices like cars, sensors, and machines. The market volume for M2M-connectionsis estimated to reach USD 27 billion in 2023.

In the end, Smart Contracts and DLT open up the possibility of a novel infrastructure for financial services, also known as Decentralised Finance (DeFi). DeFi promises an open, transparent, interoperable, and robust financial system. In this case, CBDCs can be a building block to realise connected opportunities for providers and users in an innovative way, while mitigating existing risks.

4.3 Delivery versus payment: Delivery and settlement of securities

In Europe, the traditional delivery and settlement of securities between banks and Central Securities Depositories (CSD) are done primarily by integrating ECB TARGET2-Securities (T2S) as well as the TARGET2 system of central banks. The central banks of the Euro system use TARGET2 as payment processing system. It is a real-time system of gross recording in which individual payments are continuously processed and permanently booked. T2S permits the harmonised and centralised settlement of securities against primary money in the Euro system. Securities tend to be delivered and settled as Delivery versus Payment (DvP), which works as a secure and efficient method and has the potential to mitigate the risks of failure and settlement.

Right now, traditional securities settlements, however, require several intermediaries. The DVP settlement of token or blockchain-based securities can be integrated into the function of a Smart Contract, a so-called Security Token. It automates the transfer of a Security Token against payment in real-time and can be realised without additional intermediaries. Payment with a compatible digital currency is required.

The programmable Euro on DLT basis permits the delivery and settlement of securities or automatic and seamless processing of Security Tokens. It applies, in particular, if the financial instruments are only issued digitally. The processing of transactions in securities would speed up and streamline significantly. Furthermore, a programmable Euro can be used in a Token-based ecosystem. Studies and surveys from institutions like the World Economic Forum (2015), R3 (2109), and Chain Partners (2019), estimate that around 10% of the global GDP will be tokenised, i. e., based on a DLT. Specifically, it means that tokenised assets and financial products, for example, real estate shares, can be traded faster and easier.

4.4 Monetary policy

Even if monetary policy is not one of the main reasons for introducing a CBDC in western industrial nations, compelling arguments could be derived, if so desired. This way, CBDCs could also be subjected to negative interest rates in the mid-term. Provided, that more substantial amounts of cash would be no longer available. As a result, central banks could avail of novel monetary policies during times of zero-rate policy to better react to recessions like in this current coronavirus crisis. The motivation for such a monetary policy would be controversial and perceived by opponents as the transgression of boundaries, financial repression, and expropriation of savers and fought against fiercely. Nevertheless, we wanted to mention the theoretical argument of an effective monetary policy caused by a direct negative interest rate of the CBDC by central banks.

Another monetary policy that could be facilitated by a Retail CBDC is the helicopter money discussed in the USA during the coronavirus crisis. Central banks could directly provide funds to its citizens much faster using ‘central bank wallets’. The much-discussed unconditional basic income could also be implemented easier with the help of Retail CBDC.

The theoretical advantage of improved central bank data remains a contentious issue. For example, financial flows and money distribution could be better evaluated through the use of a CBDC and lead to a better realisation of monetary policies. It means that central banks could analyse cash flows in real-time. At the moment, the supervision of financial markets occurs periodically.

Monetary policy reasons for introducing a CBDC could introduce a significant expansion of the central banks’ power. They should be thoroughly discussed and evaluated by the public as well as politics before practically implementing a specific CBDC design.

4.5 Competitiveness

Introducing a CBDC is also an issue of the future competitiveness of a domestic currency and economy. China started using a CBDC on 16 April 2020, initially on a limited scale to pay government officials in the Xiangcheng District.17 Further districts and applications are to follow from May 2020. Moreover, the private consortium of the Libra Association continues to work on the global payment solution Libra. The Libra Association also announced the reorientation of its project on 16 April 2020. Additionally, it would like to launch this year and put its Libra Coins into circulation. It is anticipated that such first movers, which are strong in resources and reach, could quickly take the lead – whether that concerns loans to finance trade or international money transfers. Once a leading position has been gained as a result of millions of new users, it is not so easy to challenge. Unfortunately, using a foreign CBDC in cross-currency transactions could also lead to ‘misuse’. For example, in Europe, the foreign central bank could gain greater insight into the transaction data of European citizens and companies. The competitiveness of a nation’s economy and the autonomy over its digital payments are incentives for the introduction of a CBDC that cannot be disregarded, particularly against the background of the fierce debate on digital sovereignty in Europe and the current dependence on global IT companies from the USA or China.

4.6 Financial stability

Another reason for introducing a CBDC is to increase financial stability by reducing bank-specific risks. Pilot projects and papers from most central banks indicate that disintermediation, i. e., the removal of the banks, is not desired. According to the ongoing discussion, this should be prevented, for instance, through appropriate design considerations during implementation.

Hypothetically, in the future, individuals, entrepreneurs, and financial institutions could carry out their transactions directly through the CBDC (instead of demand deposits with a bank). The liquidity concentration in banks would drastically reduce, thus also decreasing the systemic banking risk. Governments would no longer have to protect banks and deposits to the same extent and could thus limit, if not eliminate, the moral hazard of today’s financial industry. It would be possible to ease financial regulation as a result. The competition between banks and fintech companies would increase.

4.7 Security and resistance to manipulation

In the traditional financial system, data is frequently stored centrally on the servers of central banks or financial service providers. Conversely, the use of DLT could ensure that transaction data is stored with numerous network participants simultaneously. This approach would avoid single points of failure and make the system more resistant to cyber-attacks.

4.8 Additional motives

Depending on the features of the CBDC and the possible reduction of physical banknotes, it would be possible to implement more effective measures against money laundering, terrorist financing, and tax evasion. Moreover, CBDC could also avoid the high cost of distributing cash. Greater use of digital payments surpasses the use of banknotes and coins for hygienic reasons. For example, given the coronavirus crisis, the World Health Organization recommends using digital or even contactless payments, when possible.

5. Dealing with Digital Euro risks

5.1 Financial stability risks

Even though some central banks have already confirmed that they are working on developing a DLT-based CBDC (i. e., Retail CBDC), there is still much criticism from economists, central banks, and politicians against such a universally accessible CBDC. Critics are concerned that the introduction of a CBDC could lead to financial instability and the disintermediation of commercial banks. In an interview with the Handelsblatt, Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann argued, among other things, that the introduction of a CBDC could lead to bank runs, in which substantial liquidity is transferred from the banking sector to the central bank. As a result, the banking sector could lack sufficient liquidity. In periods of a lack of confidence in banking, there are concerns that many customers will withdraw their funds from the banks not only in cash but also in digital form. That way, frightened depositors could trigger a liquidity crisis in the banking system relatively fast and easily by transferring their funds to a secure account with the central bank. This mechanism certainly also depends on the architecture, how a CBDC would be implemented exactly (see possible solutions below).

The potential implications for lending and possible control measures should, in any case, be considered in introducing a Digital Euro. Assuming that consumers will withdraw demand deposits at their commercial banks, such as current and money market account balances, in favour of a CDBC, when a CBDC is introduced, credit operations could experience a slump.

The first interest rate follows the changes in all other market interest rates up to a specified CBDC threshold (tier 1 CBDC). However, it is specified at 1% below the deposit rate level paid on commercial bank reserves at the central bank, for instance. Thus, making the tier 1 CBDC less attractive than bank deposits. However, this tier 1 CBDC interest rate would never fall below zero (even if the deposit rate falls below 1%) to guarantee customers a non-negative interest rate.

If the above-mentioned CBDC threshold on the central bank account is exceeded, the interest rate of this tier 2 CBDC is set to zero or even to below zero. These ‘excess’ tier 2 balances never bear positive interest to prevent investment in CBDC. Instead, they reach zero during ‘normal times’ and drop below zero during periods when the reference rate is below 1% to avoid a bank run. This two-tier interest rate serves to make the CBDC attractive as a means of payment but unattractive as a store of value above a threshold. Alternatively, the convertibility of bank deposits and CBDC could be restricted. It could involve applying a quantitative ceiling or even preventing the ‘digital withdrawal’ of money from current accounts in CBDC altogether. The Bank of England already proposed such a parallel CBDC system in a paper in 2018.

5.2 Data protection concerns

Another point of criticism, often voiced by citizens and consumer advocates, is that a CBDC results in a kind of Orwellian dystopia in which central banks (and consequently governments) can track every transaction. Thus, citizens would become entirely ‘transparent’. Many fear that the introduction of a CBDC will pave the way for the abolition of cash. Additionally, there is the concern of no longer being able to conduct completely anonymous transactions.

In a working paper published in December 2019, the ECB introduces a detailed DLT-based CBDC prototype that has cash-like features. It guarantees anonymous payments, provided they do not exceed certain payment volumes, while satisfying anti-money-laundering (AML) regulations. Anonymity is implemented technically by not disclosing the identity of the customer to the central bank and the AML authority through the use of so-called anonymity vouchers. These vouchers make it possible to transfer a limited amount over a defined period anonymously. Every citizen receives a particular number of such vouchers. As soon as all vouchers have been spent, the subsequent transactions are no longer carried out anonymously. It should be noted, however, that banks have access to the transaction data; therefore, it is not anonymous. This constitutes a clear disadvantage of the prototype and should be considered in future ECB prototypes. Furthermore, all transactions are still processed through commercial banks. Transactions, therefore, do not take place on a direct peer-to-peer basis but still go through commercial banks as intermediaries. The ECB paper is a useful starting point for further analysing the anonymity of CBDCs in the context of DLT. This examination should also consider other technical solutions (e. g., private channels in the DLT framework used). Overall, these examples demonstrate that many political, economic, and ethical concerns can be tackled through intelligent technical implementation. An intensive, public discussion about the objectives of the digital euro is thus vital. This white paper provides a basis on which to do this.

6.An (interim) conclusion: Digital Euro and Europe’s sovereignty

Given the reasons provided above in favour of introducing a Digital Euro, the ECB will probably give serious thought to the introduction of a CBDC in the coming years. It is more uncertain, however, what form the Digital Euro will take, how legal, financial, and political risks will be managed, and which DLT will lay the technological foundation for this.

Regardless of whether we look at crypto-assets, private concepts for digital money, like Libra, or state CBDCs, like the Digital Euro on the blockchain: the race for digital money is in full swing. It is reasonable to expect that first movers, in particular projects strong in resources and reach, such as the digital yuan now launched in China or the Facebook project Libra, could quickly take the lead. That leading position could affect the following areas in particular: international money transfers, commerce, micro-transactions in the industrial sector, settlement of securities and other financial instruments, private transfers via messenger and social networks.

Europe is caught, both technologically and financially, between the world powers USA and China. It is therefore imperative that Europe makes rapid progress on the Digital Euro, not least in the context of the discussion about digital sovereignty. Moreover, it should take on a pioneering role so as not to become more dependent on future payment systems.